The tax consequences of selling or otherwise disposing of property used in a trade or business are very important for business owners. Taxes due on such a transaction can be dramatically different depending on whether a capital or ordinary gain or loss is generated under Section 1231, 1245, and/or 1250 of the Internal Revenue Code (i.e., the U.S tax law).

As a result, business owners considering the purchase or sale of business property need to be familiar with these tax code sections. But, as a business owner myself, I know how hard it can be to untangle complicated tax law provisions. They’re written more for lawyers and accountants than for the average business owner.

Fortunately, I’m also a CPA who’s used to deciphering the tax code and doing business-related tax planning. So, hopefully, I can help you understand how Sections 1231, 1245, and 1250 differ and how they work together to determine the tax consequences of selling business property. Once you have a handle on these tax law sections, you’ll feel more comfortable making decisions about buying, holding, or selling property needed for your trade or business.

Related: How to Invest in Small Businesses

Capital vs. Ordinary Gains and Losses

In a nutshell, Sections 1231, 1245, and 1250 of the Internal Revenue Code spell out whether a gain or loss on the sale of business property is treated as a capital or ordinary gain or loss.

But before getting into the specific rules for each of these tax code sections, it’s important to know why the distinction between capital and ordinary gains/losses matters for non-corporate business owners (e.g., sole proprietors and owners of S corporations, partnerships, limited liability companies, and other pass-through entities).

Capital Gains vs. Ordinary Income

Technically, depreciable assets, inventory, and other assets used in a business aren’t “capital assets” for federal tax purposes. However, gains from the sale of depreciable business assets can be treated as capital gains under tax code Sections 1231, 1245, and 1250.

Furthermore, as I’ll discuss later, Sections 1231, 1245, and 1250 only apply to business property held for more than one year. As a result, any gain from the sale of business property that’s treated as a capital gain will be considered a “long-term” capital gain (i.e., gains from the sale of a capital asset held for more than a year).

That’s important because, for non-corporate taxpayers, the capital gains tax rates for long-term gains are generally lower than the federal tax rates for ordinary income (e.g., wages, tips, interest, traditional IRA or 401(k) account distributions, taxable Social Security benefits, and the like). So, it’s better to have any gain from the sale of business property treated as capital gain than ordinary income.

YATI Tip: The tax rates for “short-term” capital gains (i.e., gains from the sale of a capital asset held for one year or less) are the same as the tax rates for ordinary income.

For long-term capital gains, the tax rate will be either 0%, 15%, or 20%. Which rate actually applies depends on your taxable income and filing status for the tax year.

The seven possible ordinary income rates start at 10% and go all the way up to 37%. Again, the exact tax rate that applies is based on your taxable income and filing status.

However, when comparing the same taxable income and filing status for both capital gains and ordinary income, the basic long-term capital gains tax rate will always be lower than the tax rate for ordinary income.

Special capital gains tax rates

In a few cases, a special capital gains tax rate applies. The special rates are actually maximum rates, meaning that your ordinary tax rate might still apply to short-term capital gains if it’s lower than the special maximum rate.

The special capital gains tax rates are:

- 28% for the taxable portion of a gain from selling qualified small business stock (a.k.a., “Section 1202 stock”)

- 28% for collectibles (e.g., art, coins, stamps, historic artifacts, etc.)

- 25% for unrecaptured gain from selling Section 1250 property (which I’ll discussed more below)

YATI Tip: The tax rate on capital gains for C corporations is generally the same as the rate for other taxable income (i.e., 21%).

Capital Losses vs. Ordinary Losses

When it comes to losses on the sale of business property, it’s usually better to have the loss treated as an ordinary loss instead of a capital loss.

Generally, if you have a capital loss from the sale of a capital asset, that loss can be used to offset any capital gain you might have from the sale of other assets. By offsetting a capital gain, you’re reducing the amount of gain subject to the capital gains tax. However, you must follow a certain process for offsetting capital gains with capital losses, which is known as “netting.”

If, after going through the netting process, you end up with a net capital loss, you can claim a tax deduction of up to $3,000 against your ordinary income (up to $1,500 for a married person filing a separate return). If your net capital loss is more than $3,000 (or $1,500), the excess amount is carried forward to future tax years where it’s used to offset capital gains or deducted from ordinary income until it’s all used.

On the other hand, the full amount of an ordinary loss can be used to offset ordinary income. This makes an ordinary loss more desirable than a capital loss for two reasons. First, since the ordinary income rates are greater than the capital gains tax rates, you can reduce more of the income that’s taxed at the higher rate. Second, there’s no annual cap (e.g., $3,000) on how much income can be offset with an ordinary loss. So, you can deduct a higher amount right away and not have to carry any unused deduction forward to future years.

YATI Tip: A C corporation can only use capital losses to offset capital gains. If a net capital loss remains after offsetting capital gains with losses, the excess amount is generally carried back for three tax years, and then carried forward for up to five years.

Related: Best SEP IRAs + Providers

What Is Section 1231 Property and How Is It Taxed?

Now that we have a basic understanding of the differences between capital and ordinary gains and losses, let’s dive into Section 1231 of the Internal Revenue Code.

Section 1231 Property

Generally speaking, Section 1231 applies to depreciable personal property and real property used in a trade or business and held for more than one year. This type of property is typically called Section 1231 property.

Business property that’s “involuntarily converted” (e.g., destroyed, stolen, or condemned) is also considered Section 1231 property if it’s depreciable personal property or real property held for more than a year.

Because of this broad definition, most property used in a trade or business is Section 1231 property. This includes common items like buildings, machinery, equipment, and motor vehicles, as well as less obvious things like leaseholds, livestock (but not poultry), timber, and unharvested crops.

However, some types of business property are excluded from the definition of Section 1231 property. For instance, inventory held mainly for sale to customers isn’t considered Section 1231 property. Patents and copyrights are generally not included in the definition, either.

Related: Form 8594: Asset Acquisition Statement, Explained!

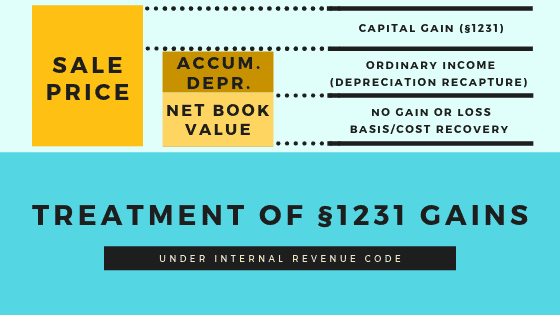

Tax Treatment of Section 1231 Property

Special tax benefits apply when Section 1231 property is sold or otherwise disposed of for a net gain or loss. (Note that the appropriate tax treatment applies to the net gain or net loss from a taxpayer’s sale of all Section 1231 property during the tax year.)

Section 1231 gains

Before looking at the tax treatment of any net gain from the sale of Section 1231 property (i.e., “Section 1231 gain”), it’s important to note that any gain treated as ordinary income under the depreciation recapture rules in tax code Sections 1245 and 1245 is not considered Section 1231 gain. Only the amount in excess of the recaptured depreciation is considered Section 1231 gain. As a result, before calculating the tax on Section 1231 gain, you must first determine whether any of your gain is ordinary income under Section 1245 or 1250—which I’ll discuss in a minute.

Once any recaptured depreciation is subtracted, the remaining Section 1231 gain generally receives long-term capital gain treatment.

However, an amount equal to any “nonrecaptured Section 1231 losses” from the previous five years (i.e., net Section 1231 losses for those years that haven’t been applied against a net Section 1231 gain) is treated as ordinary income.

Example: Assume you have a $5,000 net Section 1231 gain for the current tax year, and the following Section 1231 gains and losses for the previous five years:

| Year | Amount |

|---|---|

| Previous Year 1 | $0 |

| Previous Year 2 | -$3,000 |

| Previous Year 3 | $0 |

| Previous Year 4 | $1,400 |

| Previous Year 5 | $0 |

You have $1,600 in nonrecaptured Section 1231 losses for the previous five years ($3,000 – $1,400). Therefore, out of the $5,000 of net Section 1231 gain for the current year, $1,600 is treated as ordinary income and the remaining $3,400 is treated as long-term capital gain.

Section 1231 losses

Net Section 1231 losses (i.e., Section 1231 losses in excess of Section 1231 gains) receive ordinary loss treatment.

Related: How to Start a Retirement Plan

What Is Section 1245 Property and How Is It Taxed?

As noted above, the depreciation recapture rules under Internal Revenue Code Section 1245 and 1250 play a role in the taxation of Section 1231 property. Let’s look at Section 1245 first.

Section 1245 Property

In general, Section 1245 property is depreciable personal property used in a trade or business for more than a year. Sound familiar? It should, because Section 1245 property is basically a subset of Section 1231 property.

Section 1245 property can be either tangible or intangible personal property. So, it includes such things as patents, licenses, and other intellectual property, as well as furniture, equipment, motor vehicles, and similar depreciable property.

Other tangible property (except buildings and their structural components) is also considered Section 1245 property if it’s used as an integral part of manufacturing, production, or extraction, or of furnishing transportation, communications, electricity, gas, water, or sewage disposal services. In addition, tangible property used as a research facility or for the bulk storage of fungible commodities for any of these activities is Section 1245 property.

Section 1245 property also includes parts of real property with an adjusted basis that has been reduced by certain tax deductions, amortization, and expenditures.

Tax Treatment of Section 1245 Property

The main purpose of Section 1245 is to prevent a taxpayer from “double dipping”—in other words, from receiving two tax breaks for the same property. In this case, since the taxpayer previously claimed depreciation deductions for Section 1245 property (or could have), he or she should not also benefit from lower capital gains tax rates when the property is sold.

Section 1245 gains

Under the Section 1245 depreciation recapture rule, any gain on the sale or other disposition of Section 1245 property (i.e., “Section 1245 gain”) is treated as ordinary income to the extent of any prior depreciation allowed or allowable on the property. Note, however, that the amount treated as ordinary income can’t exceed the recognized gain on the sale or disposition.

Any remaining Section 1245 gain is treated as Section 1231 gain. In other words, it’s treated as long-term capital gain, subject to the rules for nonrecaptured Section 1231 losses.

Example: Assume you bought a piece of equipment for your business three years ago for $10,000. Since then, you’ve claimed depreciation deductions worth $3,300. During the current tax year, you sell the equipment for $7,000 (the equipment’s current fair market value). Since the depreciation deductions are subtracted from the equipment’s tax basis, the property’s adjusted basis is $6,700 ($10,000 – $3,300). That means you have $300 of Section 1245 gain ($7,000 – $6,700). Since the total amount of Section 1245 gain is greater than the recaptured depreciation, all of the Section 1245 gain ($300) is treated as ordinary income.

Section 1245 losses

Section 1245 only impacts gains. As a result, Section 1245 losses are the same as Section 1231 losses, which receive ordinary loss treatment.

Related: What’s Your Standard Deduction?

What Is Section 1250 Property and How Is It Taxed?

The other depreciation recapture rules come from Section 1250 of the Internal Revenue Code. This time, however, a different subset of Section 1231 property is targeted.

Section 1250 Property

Section 1250 property includes all real property that is subject to an allowance for depreciation and hasn’t ever been Section 1245 property. Once again, all Section 1250 property is also Section 1231 property.

If Section 1250 property becomes Section 1245 property due to a change in use, it can never again receive Section 1250 status.

Section 1250 property includes a leasehold on land or other Section 1250 property subject to an allowance for depreciation. However, a fee simple interest in land doesn’t fall into this category because land does not depreciate from an accounting perspective.

YATI Tip: Land is an example of property that’s Section 1231 property but neither Section 1245 or Section 1250 property. That’s because it’s not personal property or depreciable real property.

Tax Treatment of Section 1250 Property

The Section 1250 depreciation recapture rules differ slightly from the Section 1245 rules in that the tax rate on a portion of any Section 1250 gain is capped.

Section 1250 gain

As with Section 1245, Section 1250 prevents multiple tax breaks—depreciation deductions and lower tax rates—upon the sale or other disposition of Section 1250 property.

Assuming the Section 1250 property was purchased and placed in service after 1986, when use of the MACRS depreciation method (which uses straight-line depreciation for residential rental and nonresidential real property) started, any depreciation previously taken for the sold property is treated as long-term capital gain, but nevertheless taxed at ordinary income tax rates—but only up to a maximum of 25%.

As with Section 1245 gain, the amount taxed at ordinary income tax rates can’t exceed the amount of gain recognized on the sale or disposition. It also can’t exceed net Section 1231 gain for the year.

YATI Tip: For Section 1250 property placed in service before 1987, any “additional depreciation” previously allowed or allowable on the property is treated as ordinary income. For property held for more than one year, the additional depreciation is equal to the difference between any depreciation adjustments calculated using an accelerated depreciation method and the amount of those adjustments if the straight-line depreciation method had been used. For property held for one year or less, all depreciation adjustments are treated as additional depreciation.

As under the Section 1245 depreciation recapture rules, any remaining Section 1250 gain is treated as Section 1231 gain. That means it’s generally treated as long-term capital gain, subject to the rules for nonrecaptured Section 1231 losses.

Example: Assume you bought a building for your business six years ago for $100,000 (all values are for the building only and don’t include the land). Since then, you’ve claimed depreciation deductions using the straight-line method under MACRS worth $15,000. During the current tax year, you sell the building for $110,000. Since the depreciation deductions are subtracted from the building’s tax basis, the property’s adjusted basis is $85,000 ($100,000 – $15,000). That means you have $25,000 of Section 1250 gain ($110,000 – $85,000). Of that amount, $15,000 (i.e., the amount of depreciation) is taxed at your ordinary income tax rate, but not to exceed 25%. The remaining $10,000 is taxed at your long-term capital gains tax rate (0%, 15%, or 20%).

YATI Tip: An additional amount of Section 1250 gain is treated as ordinary income for C corporations selling or disposing of Section 1250 property. The additional amount is equal to 20% of the excess of any amount that would have been treated as ordinary income if the property were Section 1245 property over the amount treated as ordinary income under Section 1250.

Section 1250 losses

Once again, Section 1250 only concerns gains. Therefore, Section 1250 losses are the same as Section 1231 losses and are treated as ordinary losses.

Related: Estimated Tax Due Dates

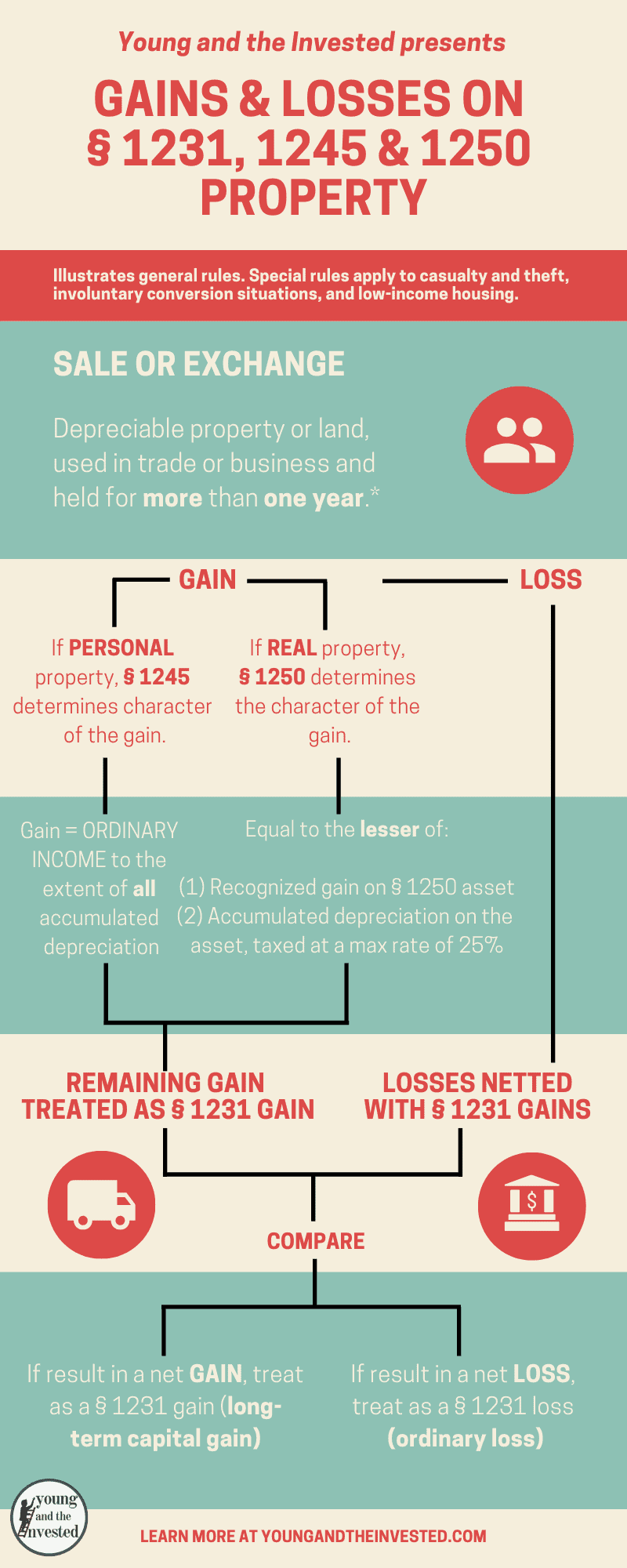

Section 1231, 1245, and 1250 Gain or Loss Flowchart

Use the following flowchart to map out the tax treatment when Section 1231 property is sold.

Related: Solo 401(k) vs. SEP IRA: What’s the Difference?

Comprehensive Example: Application of Sections 1231, 1245, and 1250

To recap, let’s run through a comprehensive example to illustrate how Sections 1231, 1245, and 1250 work together when business property is sold or otherwise disposed of by the business.

Assume you sold the following business assets, which you held for more than one year, during the current tax year.

| Property | Selling Price | Original Cost | Amount of Depreciation | Adjusted Basis | Recognized Gain/Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Printing Press | $4,000 | $6,800 | $3,200 | $3,600 | $400 gain |

| Copy Machine | $2,600 | $2,500 | $500 | $2,000 | $600 gain |

| Delivery Truck | $500 | $15,000 | $13,000 | $2,000 | $1,500 loss |

| Office Building | $75,000 | $65,000 | $3,250 | $61,750 | $13,250 gain |

You had no nonrecaptured Section 1231 losses from the previous five years.

Step 1: Calculate Recognized Gain or Loss

To calculate gain or loss for each item, start by finding the property’s adjusted basis using the following formula:

Original Cost – Depreciation = Adjusted Basis

Then compare the selling price to the adjusted basis to calculate the gain or loss.

Step 2: Calculate Section 1245 Depreciation Recapture

The printing press, copy machine, and delivery truck are all Section 1245 property. Since you sold the delivery truck at a loss, there is no depreciation recapture (but there is a $1,500 Section 1231 loss).

For the printing press and copy machine, which were sold at a gain, any accumulated depreciation (up to the amount of recognized gain) must be recaptured as ordinary income.

Any remaining gain is considered Section 1231 gain.

| Property | Ordinary Income (Amount of Depreciation) | Section 1231 Gain |

|---|---|---|

| Printing Press | $400 | $0 |

| Copy Machine | $500 | $100 |

| Delivery Truck | $0 | $0 |

| Total | $900 | $100 |

Step 3: Calculate Section 1250 Depreciation Recapture and Capital Gain

The office building is Section 1250 property. As a result, the depreciation you previously claimed for the building (but not more than the recognized gain) is taxed at ordinary income rates up to a maximum of 25%.

Any remaining gain is Section 1231 gain.

| Property | Taxed at Ordinary Rates (Up to 25%) | Section 1231 Gain |

|---|---|---|

| Office Building | $3,250 | $10,000 |

Step 4: Determine Net Section 1231 Gain or Loss

Your Section 1231 gain is then netted with all Section 1231 net losses. Remember that any gain treated as ordinary income recapture is not included in the amount of Section 1231 gain.

| Property | Section 1231 Gain | Section 1231 Loss | Netted Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copy Machine | $100 | $0 | $100 |

| Delivery Truck | $0 | ($1,500) | ($1,500) |

| Printing Press | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Office Building | $10,000 | $0 | $10,000 |

| Total | $10,100 | ($1,500) | $8,600 |

The net result is a $8,600 Section 1231 gain. Since there are no nonrecaptured Section 1231 losses from the previous five years, the full amount is treated as long-term capital gain.

Step 5: Determine Total Ordinary Income

Combine all the recaptured depreciation treated as ordinary income or taxed at ordinary income rates.

| Property | Ordinary Income (or Taxed at Ordinary Rates) |

|---|---|

| Copy Machine | $500 |

| Delivery Truck | $0 |

| Printing Press | $400 |

| Delivery Truck | $3,250* |

| Total | $4,150 |

*Taxed at maximum ordinary income tax rate of 25%.

Related: