In the lead-up to the 2024 elections, one of President Donald Trump’s many stated goals was to levy tariffs on numerous nations. He posited these taxes as “the greatest thing ever invented,” claiming they could create more jobs, lower inflation, and provide relief to the national debt.

The first part of the promise—instituting the tariffs—has been honored.

Wait, they’re gone. No, they’re back. Well, now some of them are paused. But a few others are gone. Hold up, we’re taxing China how much again?

To be honest: Tariffs are a moving target right now. I write this fully aware that by the time I’m done, some part of it will be obsolete. But if I can provide something that’s at least 80% useful to you, I’ll consider it a job well done. Sort of.

What I can tell you with 100% certainty is that 1.) The United States is now embroiled in a trade war with the vast majority of its trade partners, including its three biggest, two of which are the only two nations that share a common land border, and 2.) virtually every American will feel the impact, one way or another.

How, you ask? Well, today I’m going to answer that, and a whole lot more. Read on with me as I explain what tariffs are, how they work, what they’re used to accomplish, what Trump’s latest tariffs cover (and their current status), and how increased taxes on what we buy won’t be the only fallout of this fresh trade war.

What Is a Tariff?

A tariff is a specific type of tax that a government imposes on goods and/or services imported from other countries.

Tariffs usually are charged as a percentage of the cost that domestic purchasers pay to buy those goods or services from a foreign seller. For instance, among the earliest Trump 2.0 tariffs were a 25% levy on most goods imported from Canada and Mexico, and a 20% tax on all goods imported from China.

I’ll dive a little deeper into each country’s specific tariff situation momentarily, including updates on any changes since the tariffs were first announced. But first, I’ll run you through how tariffs broadly affect consumers and how they’re collected.

Who Pays Tariffs?

One of the biggest misconceptions about these taxes is that other countries pay the price of tariffs the U.S. levies on those countries. It’s simply not true.

The domestic businesses that import goods (retailers, for instance) pay this tax directly to the U.S. government. However, businesses don’t eat the whole cost. Far from it. They typically raise prices to account for much if not all of the import cost—meaning you, the consumer, end up indirectly paying this tax.

Indeed, shortly after the March tariffs were made official, retailers such as Best Buy (BBY) and Target (TGT) began communicating that Trump’s tax hikes could filter into retail prices “within days.”

And if the Trump tariffs are similar to the tariffs levied during the president’s first term, consumers might be shouldering the lion’s share of these costs:

“Historically, economists have found that foreign firms absorbed some of the burden of tariffs by lowering their prices, resulting in a combination of foreign businesses and domestic firms and consumers sharing the burden of tariffs,” says independent, nonpartisan think tank The Tax Foundation. “In contrast to past studies, however, recent studies have found the Trump tariffs were passed almost entirely through to US firms or final consumers.”

What does that look like, practically? Looking at the April “Liberation Day” tariffs, the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC)—another independent, nonpartisan think tank—projected that the taxes would “reduce disposable income for the average taxpayer by about $2,900 in 2026.” The lowest-income 20% of households would be worse off by an average of $500, while the wealthiest 20% would pay an additional $10,460 thanks to the tariffs.

Do you want to get serious about saving and planning for retirement? Sign up for Retire With Riley, Young and the Invested’s free retirement planning newsletter.

An Example of How Tariffs Work

Here’s a hypothetical example to demonstrate how tariffs work:

- A U.S. grocer normally pays a Canadian supplier $20 per jug of maple syrup, then sells it to consumers for $22.

- The U.S. levies a 25% tariff on all goods imported from Canada, meaning that jug of maple syrup is subject to a 25% tax.

- The next time the U.S. grocer imports maple syrup, it still pays the Canadian supplier $20 per jug. However, when that maple syrup reaches an American port of entry, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents also collect the 25% tariff (so, an additional $5 per bottle) as that syrup clears customs.

- The grocer, now paying $25 per jug of maple syrup, decides to pass 80% of the tariff costs (so, $4) on to the consumer. It absorbs 20%, which cuts into its profit margins.

- The consumer now pays $26 for the jug of maple syrup—an 18% increase from the $22 they used to pay.

Related: 8 Ways Higher Tariffs May Lead to Higher Costs for Americans

Trump’s 2025 Tariffs, Piece by Piece

I previously wrote this as a country-by-country look at the Trump tariff situation, but the “Liberation Day” tariffs—which added some 180 countries and territories to that tally—made that impractical.

So instead, I’m going to look at the tariffs across groupings that make the most sense.

Just note, before reading on, that these tariffs are … well, fluid. The landscape has shifted substantially in just a couple of months. Tariffs have been paused, delayed, and even killed. There are a lot of moving parts. But we’ll do our best to update this story when and if the White House changes its approach on the tariffs listed here.

1. Global blanket tariffs

- Status: Active

- Enactment date: April 5

- Rate: 10%

On April 2, President Trump announced a two-part set of tariffs:

- A 10% tariff on all countries

- “Individualized reciprocal higher tariff[s]” on the countries with which the United States has the largest trade deficits

The former tariff, referred to as the 10% “blanket” tariff, is as straightforward as it gets. Imports from every country will be subject to an additional 10% tariff.

That said, despite an April 5 enactment date, U.S. Customs and Border Protection posted a bulletin that outlined a 51-day grace period for cargoes loaded before April 5, as long as they arrive in the U.S. before May 27.

Even as the U.S. says it may negotiate many of the latter “reciprocal” tariffs, which I’ll outline momentarily, the 10% tariff is expected to remain in place.

Related: Will Tariffs Raise Consumer Prices? 7 CEOs Weigh In

2. Global reciprocal tariffs

- Status: Delayed

- Enactment date: N/A

- Rate: Varied

The “reciprocal” tariffs, which were expected to impact 57 trade partners as of its announcement, are a stickier wicket to explain.

“Reciprocal” in name only

President Trump explained that “reciprocal” means “they do it to us and we do it to them. Very simple. Can’t get any simpler than that.” But it’s not that simple. Truly reciprocal tariffs would be an exact-match tariff based on the tariffs other countries charged us. If, say, the U.K. had a blanket 10% tariff on U.S. goods, a “reciprocal” U.S. tariff would be 10%.

The tariffs we’re charging other countries are not that.

Hat tip to James Surowiecki, contributing writer for Fast Company and The Atlantic, and Editor at The Yale Review, who was among the first to figure out where the “reciprocal” tariff numbers actually came from: “They didn’t actually calculate tariff rates + non-tariff barriers, as they say they did. Instead, for every country, they just took our trade deficit with that country and divided it by the country’s exports to us.”

That was indeed the case. The U.S. then divided that number by two to get America’s “reciprocal” tariff rate. Anyone whose formula came out to below 10% was set to a bar of 10%.

Response to this was … well, blunt. The Tax Foundation, for one, called the calculations “nonsense.”

“No factors discussed by the administration in these documents or anywhere else (like tariffs, digital services taxes, value-added taxes, or monetary policy) play any role,” the Tax Foundation writes. “For example, Singapore is a relatively free-trade-oriented country, while Brazil makes considerably more use of tariffs and other trade manipulations. However, both end up with the 10 percent rate because of their goods trade balances with the U.S. By contrast, Vietnam, which exports a great deal to the U.S. but has also worked to make its policies amenable to the U.S., gets no credit for the effort.

In short: These are “reciprocal” tariffs in name only. In many cases, the tariffs are much, much higher than what other countries charge on our exports. You can see a full list of proposed tariffs by country here … however, we’re not displaying the White House’s figures for “tariffs charged to the U.S.” because they’re factually inaccurate.

Even then, don’t expect these numbers to last. The tariffs—which include wild figures like a 46% tariff on Vietnam and a 31% tariff on Switzerland—have been paused for 90 days, with the White House claiming that they are in negotiations with several countries to bring down the rates.

Tech Exemptions

The Trump administration has included a wide number of technological-product categories in its exemption list from the “reciprocal” tariffs. A few examples include:

- Laptops and desktop computers

- Smartphones

- Semiconductor manufacturing equipment

- Computer parts and accessories

- Flat-panel displays

- Unmounted chips, dice, and wafers

However, these products still appear to be subject to the blanket tariffs.

And the pause could very well be temporary. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick told ABC News’ This Week that electronics are “exempt from the reciprocal tariffs, but they’re included in the semiconductor tariffs, which are coming in probably a month or two.” He says the coming tariffs, which will be among other business-specific taxes, “[will] not be available for negotiation.”

Related: When Should You Take Social Security?

3. Global automobile tariffs

- Status: Active (CBU vehicles), Pending (auto parts)

- Enactment date: April 3 (CBU vehicles), May 3 (auto parts)

- Rate: 25%

In late March, before the “Liberation Day” tariffs, Trump announced a 25% blanket tariff on all light-vehicle imports from all countries.

The tariff is split into two parts:

- A tax on “completely built up” (CBU) vehicles, which went into effect on April 3

- A tax on auto parts, which is due to come into effect no later than May 3, 2025

There’s still a great deal of uncertainty around these tariffs, though. From S&P Global Mobility:

“The U.S. Commerce Department is developing a process to adequately process this element. As a result, the auto parts tariff may not apply to Canada or Mexico until that happens. In our assumptions for the April 2025 forecast, however, we expect this issue will be resolved early in the second half of 2025 and that the 25% auto parts tariff will move forward.”

On top of that, the president recently said he’s considering exempting some car companies from the 25% tariffs, on a temporary basis, to give them more time to move manufacturing to the U.S. That said, automakers have largely voiced doubts about a wholesale transition, citing the unpredictability of tariff policy among other concerns, and said any changes they might make would require heavy investment and years to implement.

Related: Are You Financially Stable? 10 Signs of Financial Health

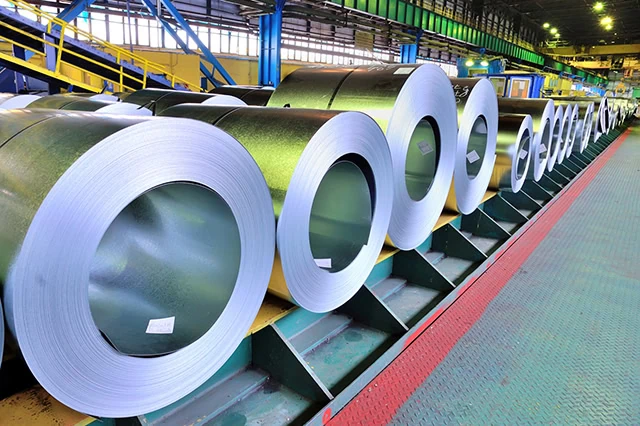

4. Global steel and aluminum tariffs

- Status: Active

- Enactment date: March 12

- Rate: 25%

One of Trump’s earliest tariffs was a resumption of 25% tariffs on steel and an increase in aluminum import taxes to 25%.

However, it was more than just a “resumption”—in some ways, it was an expansion.

The announcement also stopped exemptions from countries such as the EU, Canada, Mexico, Japan, South Korea, and other countries. It also expanded the tariffs to cover “derivative” products (not just the metals themselves, but products made out of steel or aluminum). And there are no exemptions for specific forms of the metals that the U.S. can’t produce in sufficient numbers.

“[Price] hikes for industrial inputs like steel and aluminum hurt a broad swath of downstream manufacturers across the United States, from the auto and aerospace sectors to food producers and the oil and gas sector,” John G. Murphy Senior Vice President, Head of International, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, wrote in late March. “For every job in steel production, there are roughly 80 Americans employed by manufacturers that use steel as an input, and the ratio of upstream-to-downstream employment in aluminum is 1-to-177.”

Related: How Are Social Security Benefits Taxed?

5. Chinese tariffs

- Status: Active

- Enactment date: March 4 (20% blanket tariff), April 9 (125% “reciprocal” tariff)

- Rate: 145% cumulatively

While China, our third-largest trading partner, was included in the “reciprocal” tariffs, we’re breaking it out separately. That’s because of the exceptionally high rate, and the fact that imports from the nation are subject to a second separate levy.

China was the target of one of Trump’s earliest tariffs—a 20% blanket rate that went into effect on March 4. However, on “Liberation Day,” Trump announced an additional 34% tax on Chinese goods. China matched that number, prompting Trump to raise the tariff by another 50 points to 84%. China again responded in kind, and Trump retaliated by hiking the “reciprocal” tariff to 125%.

Add the two taxes together, and you get a wild 145% total tariff on Chinese goods.

6. Canadian and Mexican tariffs

- Status: Active (USMCA-noncompliant), Delayed (USMCA-compliant)

- Enactment date: March 4 (USMCA-noncompliant), Delayed (USMCA-compliant)

- Rate: 25%

On March 4, President Trump instituted a 25% blanket tariff on virtually all goods from Canada and Mexico, our largest and second-largest trading partners, respectively.

Trump quickly pivoted, however. On March 6, he limited the 25% tariffs to goods not compliant with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which is the trade agreement that Trump himself brokered during his first term as a replacement of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

What is USMCA-compliant? Typically, if the product is fully sourced and made in either of the nations, it won’t be subject to tariffs. That means many agricultural products will likely be exempt—though the White House recently announced that it will put a 21% tariff on most tomatoes coming from Mexico on July 14.

However, foods that are somehow processed in Canada or Mexico (say, pickled or candied) but use imported foods from other countries might still be subject to the tariff. Many manufactured goods will also likely be taxed if they use a heavy amount of imported materials.

Also on March 6, Trump announced a lesser 10% tariff on Canadian energy resources, such as oil and natural gas, as well as on any potassium salts (potash) imported from Canada and Mexico.

7. “Secondary” Venezuelan oil tariffs

- Status: Active

- Enactment date: April 2

- Rate: 25%

One of the lesser-talked-about tariffs was brought up in late March and implemented in early April.

This “secondary tariff” is a 25% tax on all goods from any country that imports Venezuelan oil, whether directly from Venezuela or indirectly through third parties. And the tariff will apply for up to one year (if not sooner) after the cessation of such imports. The tax would be on top of any other tariffs.

This tariff is noteworthy for a couple reasons.

For one, this particular tax wasn’t designed to achieve any trade aim, but instead was a foreign-policy weapon aimed at Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro. Its damage also was concentrated around China, the largest importer of Venezuelan oil.

“Adapting the idea of secondary sanctions to tariffs—and again using tariffs to achieve goals unrelated to trade—in our view further reduces the likelihood that April 2 is the peak of trade uncertainty,” Evercore ISI analyst Sarah Bianchi wrote in a March 26 note.

Retaliatory Tariffs

Tariffs can significantly damage demand for a nation’s goods. So, as you can imagine, countries often don’t take these kinds of measures sitting down. Quite the opposite: They frequently clap back with tariffs of their own.

The impact of other nations’ tariffs is different on our end. Many U.S. consumers might never notice that a country has suddenly levied a tax on some of our imports.

But American businesses will.

Here’s a very quick look at some of the most significant retaliatory tariff news:

- Canada: In March, Canada announced 25% tariffs on $30 billion in goods originating from the U.S., including live poultry, meat, pork, milk, cream, eggs, numerous fruits and vegetables, wine, beer, spirits, tobacco, various toiletries, tires, wood products, apparel, tools, and more. Following the steel and aluminum tariffs, Canada announced tariffs on another roughly $30 billion in imported goods. And starting April 9, Canada will place a similar 25% tariff on U.S. vehicle imports (but not auto parts) that don’t meet USMCA requirements.

- China: In February, China announced 10%-15% tariffs on crude oil, liquefied natural gas, petroleum, coal, farm machinery, motor homes, trucks, and more. In March, the country announced 10%-15% tariffs on chicken, wheat, corn, cotton, sorghum, soybeans, beef, seafood, fruit, vegetables, dairy products, and more. Following “Liberation Day,” China announced a 34% blanket tariff rate on U.S. goods, which it later upped to 84%.

- Mexico: In March, Mexico said it would respond to America’s tariffs with its own 25% levy on U.S. goods. However, it did not follow through after U.S. tariffs on Mexican goods were limited to USMCA-noncompliant imports.

- European Union: While the EU is in negotiations over the reciprocal tariffs, it recently announced it would tax American toilet paper, soybeans, makeup and other products if talks break down.

Related: The 15 Best ETFs to Buy for a Prosperous 2025

Other Impacts

The consequences of tariffs extend past the tit-for-tat percentages we’ve talked about above.

China, for instance, has stopped exporting rare earths—metals such as neodymium and cerium that are critical components within technology, automobiles, aerospace, and defense. China, which produces between 60% to 70% of the world’s rare earths, has cut off not just the U.S., but the rest of the world.

Also, the tariffs are effectively undoing the work of numerous trade deals and injecting instability into global trade. As a result, the U.S. looks like an increasingly unreliable partner, prompting nations to explore dealing more with one another. For instance, Beijing’s ambassador to Canada has said China wants to step up trade with our northern neighbor. And Canada’s trade minister has said they want to strengthen ties with the European Union.

Lastly, even if every tariff were to eventually vanish, the economy is still suffering damage from the chaotic rollout of these taxes.

“The effects of uncertainty can be severe,” says the Tax Policy Center. “As businesses and consumers pause or scale back their spending simply because they do not know what is coming next, the economy begins to slow. Businesses can also reduce hiring, as they need fewer workers to meet reduced demand for their products, compounded by uncertainty about future demand. This is how uncertainty can lead to recession.”

Tariffs Are Hardly New

While the March and April tariffs have received massive media attention, they’re not the only taxes Trump has levied. In February, for instance, he reinstated a 25% tariff on steel imports (originally instituted during his first term) and increased tariffs on aluminum imports from 10% to 25%.

And Trump is hardly the only president to use tariffs.

In September 2024, then-President Joe Biden raised existing tariffs on a host of goods made in China, including a 100% tariff on electric vehicles (EVs), 25% on lithium-ion EV batteries, and 50% on semiconductors and solar cells. The Obama administration had imposed 35% tariffs on tires imported from China. George W. Bush enacted tariffs on a variety of steel products. Heck, John F. Kennedy placed tariffs on imported steel.

In short: Tariffs themselves are nothing out of the norm.

But Trump’s tariffs are noteworthy for two reasons: 1.) They’ve been levied on whole countries, not just targeted materials, and 2.) They’ve been levied on a number of allies and trade partners. Indeed, in the case of Canada and Mexico, the tariffs are a bizarre turn of policy just a few years after Trump himself negotiated and agreed to the USMCA.

Related: 8 Best Wealth + Net Worth Tracker Apps [View All Your Assets]

Why Do Countries Impose Tariffs?

Tariffs can be put into place to accomplish one or more of several goals:

- Protecting domestic industries: As I outlined above, tariffs make imported goods more expensive. That in turn might encourage consumers to buy locally produced alternatives.

- Political/economic leverage: Governments can also use tariffs to apply pressure to foreign nations, whether that’s to secure better trade conditions or to ensure compliance with other policies. For instance, Trump has cited curbing the fentanyl trade among the primary drivers of his tariffs.

- Retaliation against unfair trade practices: Tariffs also can be used to try to dissuade a foreign nation from engaging in unfair trade practices such as dumping goods, or in retaliation for poor trade conditions or even tariffs.

- Improve national security: Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows the president to raise tariffs on imports believed to threaten national security. For instance, tariffs could be used to ensure the U.S. doesn’t rely (too heavily, or at all) on trading with foreign countries for critical military products.

- Raising government revenues: Given that tariffs are simply taxes, they can be used to fill the government’s coffers.

While all of these are fair enough aims, that doesn’t mean tariffs always meet the moment. Tariffs can backfire, sometimes spectacularly.

For instance, tariffs might increase domestic consumption of certain goods in the short term, but ultimately result in lower baseline demand as some consumers simply find other alternatives. Tariffs are inflationary by their very nature. They can cut into the profits of companies that try to shield their customers from the full brunt. And using tariffs liberally against trade partners can damage those relationships over the long term, driving those countries to look elsewhere for less combative partners and even compelling them to enact retaliatory tariffs in response.

Do you want to get serious about saving and planning for retirement? Sign up for Retire With Riley, Young and the Invested’s free retirement planning newsletter.

Who Decides Whether the U.S. Will Charge Tariffs?

It’s a complicated question, and one that really isn’t relevant to most people’s financial realities, which is why I saved it for last.

The Congressional Research Service—a governmental public policy research institute that actually operates in the Library of Congress—has an excellent overview. But in short:

The Constitution explicitly gives the power of outlining and collecting tariffs to Congress. However, over the years, Congress has shared increasing amounts of that power and responsibility off to the president. Indeed, the last tariff act in which Congress set rates was the Tariff Act of 1930 (aka the Smoot-Hawley Tariff).

Most of the regulations that give America’s president authority over taxes do so under specific conditions. For instance, to institute the blanket tariffs on Canada and Mexico, Trump is invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA)—a national security law meant “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.”

However, taking this “emergency” route comes with a number of headaches. For one, the U.S. has faced logistical challenges in collecting tariffs on “de minimis” imports ($800 or less), such as shipments from sites like Temu that are made directly to consumers. Trump’s original order, in February, authorized the collection of tariffs on de minimis imports, but it quickly became clear U.S. systems weren’t capable of handling de minimis taxes, so they’ve been indefinitely suspended until “adequate systems are in place to fully and expediently process and collect tariff revenue.” An updated order in April stated the U.S. would eliminate de minimis for China and Hong Kong starting May 2, 2025.

![How to Get Free Money Now [13 Ways to Earn Money Today] 34 how to get free money](https://youngandtheinvested.com/wp-content/uploads/how-to-get-free-money-600x403.webp)

![8 Best Debit Cards for Teens [Reviewed by a CPA + Father] 36 best debit cards for teens hires](https://youngandtheinvested.com/wp-content/uploads/best-debit-cards-for-teens-hires-600x403.webp)